Terry Jenner’s life story is far bigger than the nine Tests that appear beside his name. It is the story of a gifted wrist-spinner who learned spin bowling in backyards, challenged international batting line-ups, then vanished almost completely from the sport before returning through a back door as one of the most influential spin coaches in modern cricket. It is a story with two acts: the first dominated by enormous potential overshadowed by inconsistent selection and emotional frustration, and the second shaped through collapse, addiction, prison and redemption. In modern cricket, Shane Warne’s success is often seen as a miracle of talent, but part of that miracle came from Jenner’s teachings. His legacy stands on both sides of triumph and failure, proving that mistakes need not destroy a life if lessons are accepted honestly.

Early Life and Family Background in Western Australia

Terence James Jenner was born on 8 September 1944 in Mount Lawley, Perth, before spending most of his childhood in the rural town of Corrigin. His father owned a shop, and his family worked long hours to keep the business functioning. Jenner grew up surrounded by farm workers, small business owners and working-class families who relied on one another through tough seasons and uncertain income. This practical upbringing shaped him. He did not speak the polished language of elite sports schools; he spoke directly and honestly, sometimes stubbornly. The early years were simple in circumstance but complex in emotional formation.

Education never captivated Jenner. He left school early, not because he lacked intelligence, but because he leaned towards physical action and direct experience. Cricket came naturally in that rural environment; dusty backyard pitches and makeshift stumps replaced formal training facilities. Without coaches, he developed his wrist-spin instinctively, experimenting through repetition and curiosity. His deliveries began dipping and twisting unpredictably long before he understood the mechanical language of revs, drift or release angles.

His break came unexpectedly. At 18, during a net practice session at the WACA Ground, he bowled a googly that dismissed England captain Ted Dexter. News of the young wrist-spinner capable of turning the ball both ways spread quickly around Western Australian cricket circles. Selectors suddenly had a reason to watch him, and state cricket opened up as a possibility.

Jenner went on to build his own family later in life, with a daughter named Trudianne, a granddaughter Ashlea, and a second wife named Ann, who supported him particularly during his health issues and the most demanding stages of his coaching career. Family connections would eventually form emotional pillars helping him in his years of recovery from addiction and prison.

First-Class Cricket: Western Australia, South Australia and County Stints

Terry Jenner began his first-class career for Western Australia in 1963. It was a difficult environment for a young spinner; WACA conditions in the 1960s favoured pace over spin, built on bounce, hardness and seam movement. Jenner could not secure a regular place. He played sporadically across four seasons, never fully convincing selectors long enough to give him consistency.

In 1967-68, he made a choice that altered his trajectory. He moved to South Australia to bowl on the Adelaide Oval, a pitch far more receptive to spin than Perth’s fast tracks. It proved a successful transition. Over the next decade, Jenner cemented his place in the state side. He formed a strong partnership with off-spinner Ashley Mallett, a relationship spoken of fondly in later years. Mallett bowled tight lines and created pressure, allowing Jenner to experiment with flight and deception.

Observers described Jenner’s bowling as visually distinctive. He used a high release, generating loop and drift. The ball hung in air momentarily, teasing batters forward only to dip late. His googly made an impression when disguised within sequences of leg-breaks. Opposition players later recalled the difficulty of predicting what Jenner would deliver because he liked varying speed off the pitch rather than through arm speed alone.

Jenner also spent time in England, playing Lancashire League cricket for Rawtenstall and Minor County cricket for Cambridgeshire. Those stints allowed him to encounter different batting approaches and different climate conditions where swing, moisture and lower bounce influenced tactics. These experiences deepened his technical understanding and later provided valuable coaching insight when working with young spinners struggling to adapt to conditions outside Australia.

Across 131 first-class games, Jenner took 389 wickets at around 32.18, while contributing useful lower-order runs. Statistically, he was not dominant, but his style and influence on teammates were far greater than the numbers suggested.

Test Selection, Highlights and the John Snow Incident

Jenner made his Test debut in the 1970-71 Ashes series. His first major success came at Brisbane, where he dismissed English batsmen John Edrich and Geoff Boycott, both respected and technically strong players. It was a start that showed promise.

Over the next few years, however, his Test career remained irregular. Australian selectors in the early 1970s tended to treat wrist-spinners as optional rather than fundamental. Jenner’s talent therefore came with doubt. He was selected, then dropped, then recalled sporadically based not just on form but also on conditions, weather, opposition make-up and internal politics.

A dramatic moment in his Test career occurred during the Ashes at Sydney, when he ducked into a bouncer delivered by England fast bowler John Snow. The ball struck him in the head. Jenner retired hurt, bleeding and shaken, then returned later to bat through pain. Many cricket writers later pointed to that incident as evidence of Jenner’s willingness to fight through discomfort.

His best bowling performance arrived in the 1972-73 West Indies tour. In the final Test in Trinidad he took five for ninety, removing Roy Fredericks, Alvin Kallicharran and Rohan Kanhai. His bowling that day showcased peak control and variation.

He also contributed significantly with the bat in the 1974-75 Ashes Test at Adelaide. Australia slumped to 84 for 5, but Jenner fought for 74 runs from number eight. It became one of his most remembered achievements because it showed resilience and fighting character beyond his primary skill.

Jenner played against a Rest of the World XI in 1971-72 after South Africa’s tour was cancelled. Facing batsmen like Garry Sobers, he displayed courage through flight and daring angles of spin.

His final Test came in the 1975-76 series against the West Indies. By then his international career featured nine Tests and 24 wickets. For a spinner with his natural gifts, nine Tests felt insufficient.

Selection Controversy, Missing Tours and Bradman Reprimand

Several controversies surrounded Jenner’s limited international representation. During the West Indies tour farewell, he faced allegations from a tour manager accusing him of inappropriate contact at a party. Jenner denied the claim and suggested it was used to justify dropping him from future squads.

In 1975 he was omitted from the England tour. He expressed his disappointment publicly in newspaper comments questioning selection logic. Sir Donald Bradman, then chairman of the Australian Cricket Board, reprimanded Jenner for speaking publicly against selectors.

In 1977, Jenner missed out on a World Series Cricket contract. Many players with fewer Tests were selected. Jenner watched opportunity pass while he spiralled emotionally.

Decline, Addiction and Crime

Once first-class cricket ended in 1977, Jenner struggled with purpose. Gambling filled the void. Horse racing and betting became his routine. Alcohol influenced his decision-making. Financial pressures mounted. Jenner borrowed money and chased recovery bets.

Eventually, he stole money from his employer to cover debts. Investigations revealed missing funds and unauthorised withdrawals. He confessed in court.

In 1988, Jenner received a six-and-a-half-year sentence in Adelaide. He served about 18 months before parole.

Jail Sentence and Turning Point

Terry Jenner’s life unravelled in 1988 when financial audits exposed repeated unauthorised withdrawals used to cover gambling debts. He confessed in Adelaide court and received a six-and-a-half-year prison sentence, serving about eighteen months before parole. Prison became a psychological reset rather than an ending. Inside, he attended counselling, read daily and began writing to understand the roots of his addiction. Jenner later said jail “was the beginning of my new life,” because enforced routine and reflection replaced the chaos of gambling. When he walked out on parole, he carried clarity, accountability and the decision to rebuild everything through cricket coaching, shaping the second chapter of his life.

Prison and Psychological Reset

Jenner later said prison was both the worst and most productive period of his life. He described the early days as overwhelming, full of shame and loneliness, but gradually routine replaced chaos. He began counselling, reading and writing poetry. Prison forced stillness where gambling once forced frenzy. He acknowledged later that prison saved him.

He said, “Going to prison was the beginning of my new life,” and added, “I began to rebuild myself inside.”

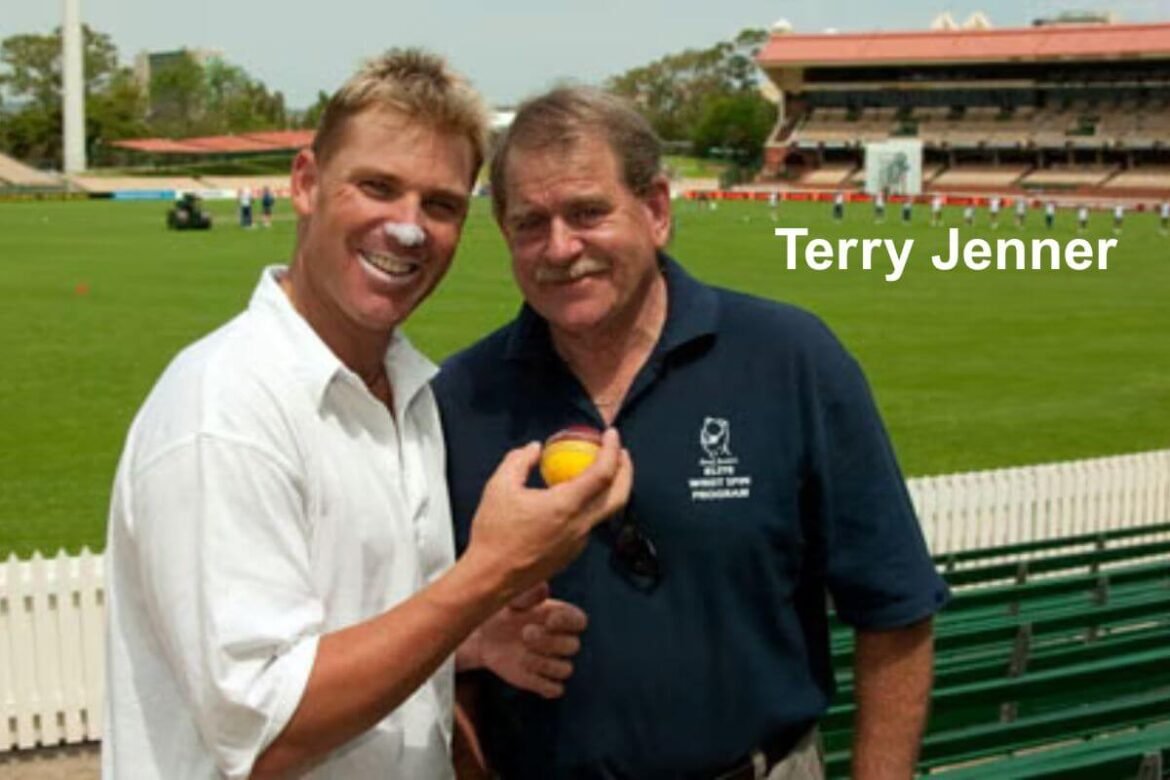

Coaching, Shane Warne and Spin Revival

After release in 1990 Jenner accepted a position at the Australian Cricket Academy in Adelaide. That same year a young Victorian spinner named Shane Warne arrived. Jenner noticed immediately that Warne’s wrist produced extraordinary spin. Warne had natural talent but lacked control and discipline.

Jenner taught Warne how to control speed through flight, how to vary drift and how to plan dismissals ahead of time. Warne later said Jenner’s guidance played a major role in his development, especially after recovering from shoulder injuries.

Jenner also worked with ECB spin programs in England and offered private training to county bowlers and young spinners in Ireland. He conducted leg-spin masterclasses worldwide. Through coaching he earned respect that playing had not delivered.

Influence on Coaching Culture in Australia

When Jenner began coaching after prison, Australian cricket’s approach to spin was largely reactive rather than developmental. Fast bowling dominated, and wrist-spin was seen as unpredictable and difficult to manage. Jenner changed that mindset from the ground up. He introduced structured spin sessions at the Australian Cricket Academy, breaking down wrist-spin into components: grip, release, body alignment, drift, revs, and mental patience. He emphasised planning overs ahead and reading batters, concepts that were rare in Australia before Warne’s era. Many young bowlers later said Jenner was the first coach who treated leg-spin as a craft with its own science rather than a trick. His philosophy gradually travelled through state programs and club cricket, influencing generations of spinners long after his playing career had ended.

Lifestyle, Finances and Net Worth

Jenner lived modestly in Adelaide with his second wife Ann. Cricket salaries in the 1970s were modest, and years lost to gambling removed savings. Later he earned comfortably through coaching and commentary. His estimated net worth ranged between AUD $400,000 and $700,000.

Health Decline, Testimonial Dinner and Death

In April 2010 Jenner suffered a major heart attack while in England. He spent nine weeks in hospital and returned to Australia. His health continued declining.

In October 2010 a testimonial dinner in Adelaide brought more than 400 attendees, including Shane Warne, Ian Chappell, Doug Walters and Ian Healy, honouring him for teaching craft and resilience.

On 25 May 2011, Jenner died in Adelaide at age 66 following prolonged illness associated with complications from the heart attack.

Personality, Character and Reputation

The Guardian obituary described Jenner as colourful and watchable, matey, opinionated, sometimes argumentative, and always interesting. He accepted his mistakes publicly and spoke honestly about addiction and poor decisions. He appreciated humour, conversation and emotional candour. He became known as a “lovable rogue,” and especially in coaching circles, a deeply thoughtful cricket thinker.

Legacy Beyond Shane Warne

Although Shane Warne was his most famous student, Jenner’s influence extended well beyond one cricketer. He worked with county bowlers in England, contributed to ECB spin-development programs and held clinics in Ireland and South Africa. Coaches began inviting him to speak not just about technique but about resilience, addiction and life after sport. Young bowlers respected that he never pretended to be perfect; he spoke honestly about failure and responsibility. Several Australian spinners who came through the 1990s and early 2000s systems claimed Jenner helped them understand drift, variation and over-by-over strategy. His lessons appear in coaching manuals and training programs that never mention his name publicly, but still reflect his voice. More than wickets or averages, Jenner’s greatest achievement was giving spin bowling a pathway, structure and language in Australian cricket that had not existed before he arrived.

Conclusion

Terry Jenner’s story reminds us that careers are not always measured by statistics or contracts. His nine Tests and 24 wickets told only a fraction of his journey. The real impact came later, in how he confronted addiction, accepted punishment and rebuilt his life with honesty. Jenner did not hide from his worst moments; instead, he learned from them and used that experience to mentor others. His influence on Shane Warne and countless young spinners reshaped modern wrist-spin thinking in Australia and overseas. For every cricketer who has been dropped, doubted or lost, Jenner’s life demonstrates that redemption is possible and that knowledge gained through hardship can outlast fame. His legacy is not a footnote in Australian cricket history, it is a reminder that resilience, not perfection, defines life and sport.

FAQs

Who was Shane Warne’s mentor?

Shane Warne’s early development as a leg-spinner was significantly shaped by Terry Jenner. After Jenner’s release from prison in 1990, he joined the coaching staff at the Australian Cricket Academy and took under his wing a young, talented but raw spinner — Shane Warne — teaching him wrist-spin technique, flight, drift, mental discipline, and match-planning.

What was Terry Jenner known for?

Terry Jenner was known for being a skilled wrist-spin and leg-break bowler with a strong googly, a first-class cricketer for South Australia, a Test player for Australia in the early 1970s, a controversial figure whose gambling and financial difficulties ended in a criminal conviction, and most importantly a spin-bowling coach whose mentorship helped revive leg-spin via players like Shane Warne.

Who is the wife of Terry Jenner?

Terry Jenner was married twice. His second wife was named Ann, who stood by him during his coaching career and later health challenges. He also had a daughter, Trudianne, and a granddaughter, Ashlea.

Why did Caitlyn Jenner not go to Brody’s wedding?

That question doesn’t relate to Terry Jenner. It refers to a different Jenner family. There is no public record linking Terry Jenner to any individuals named Caitlyn or Brody in popular media.

What is Kylie Jenner diagnosed with?

This also does not refer to Terry Jenner. It appears to reference members of a separate Jenner family (celebrity family). There is no credible publicly known medical diagnosis for someone named Kylie Jenner in any reliable source related to Terry Jenner.

What did they find in Kris’s scan?

This question seems to reference a pop-culture or media story unrelated to Terry Jenner. There are no records connecting Terry Jenner to any “Kris scan” or similar events in public documents about his life.

What was Bruce Jenner’s disability?

This question is unrelated to Terry Jenner. It appears to refer to another public figure named Jenner. There is no evidence that Terry Jenner had a disability described publicly under that name.